Biography

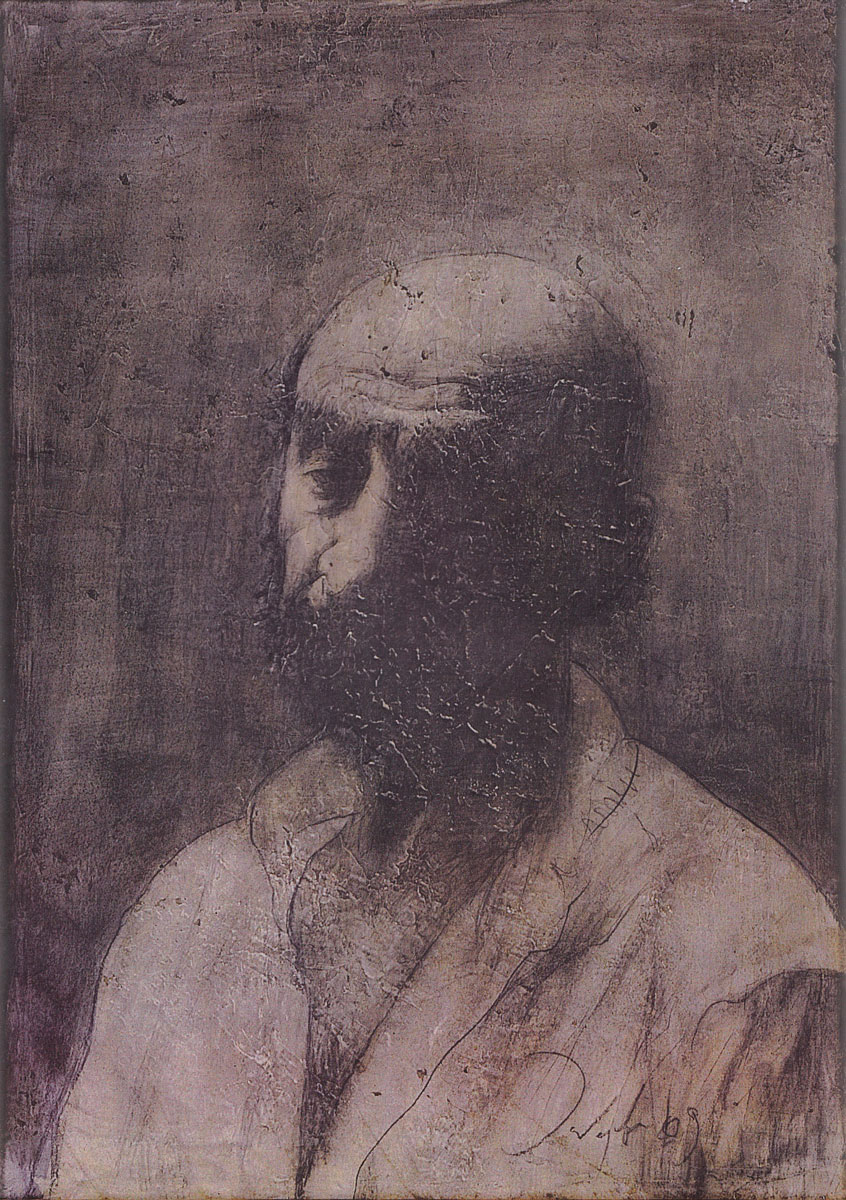

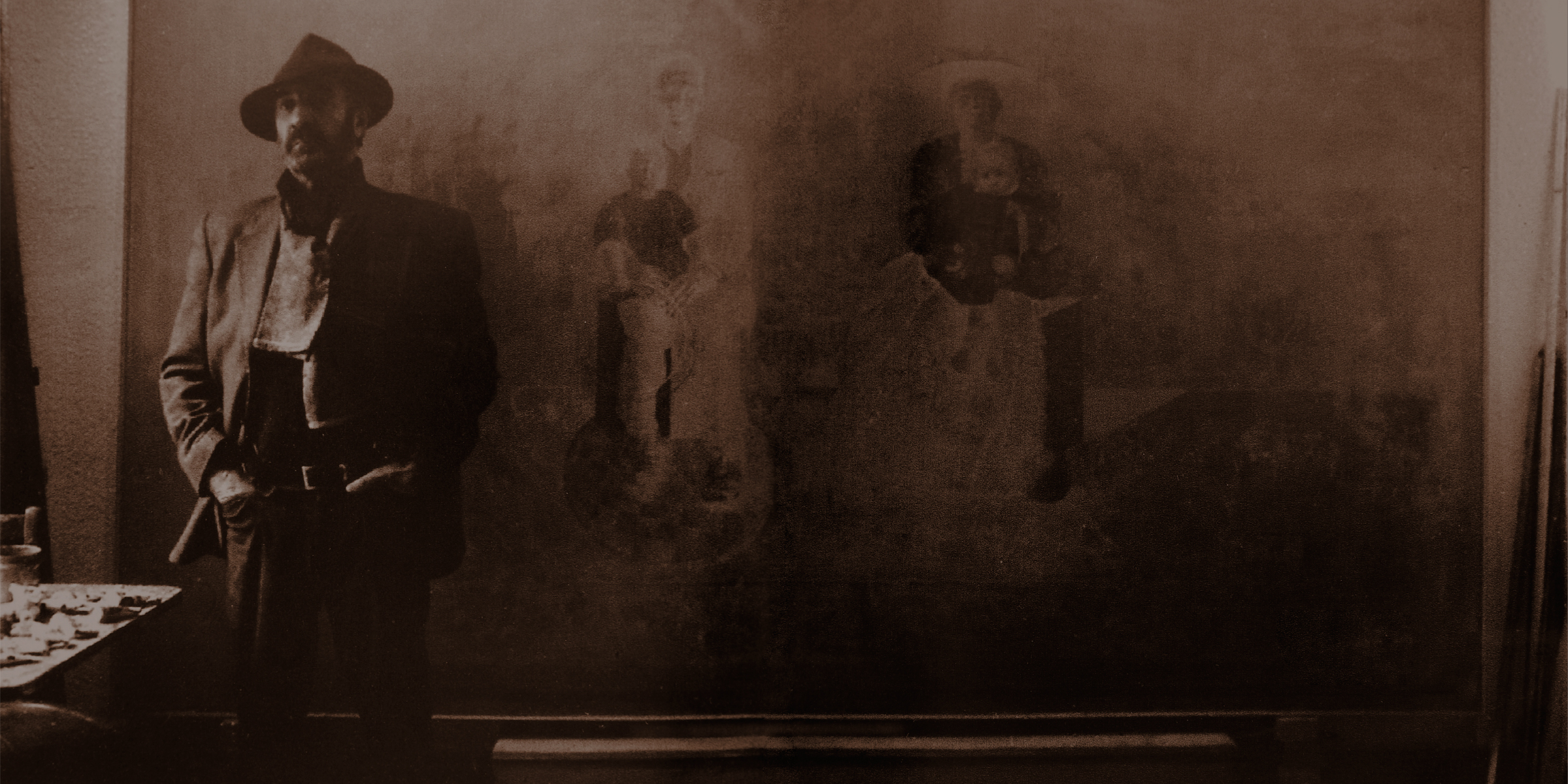

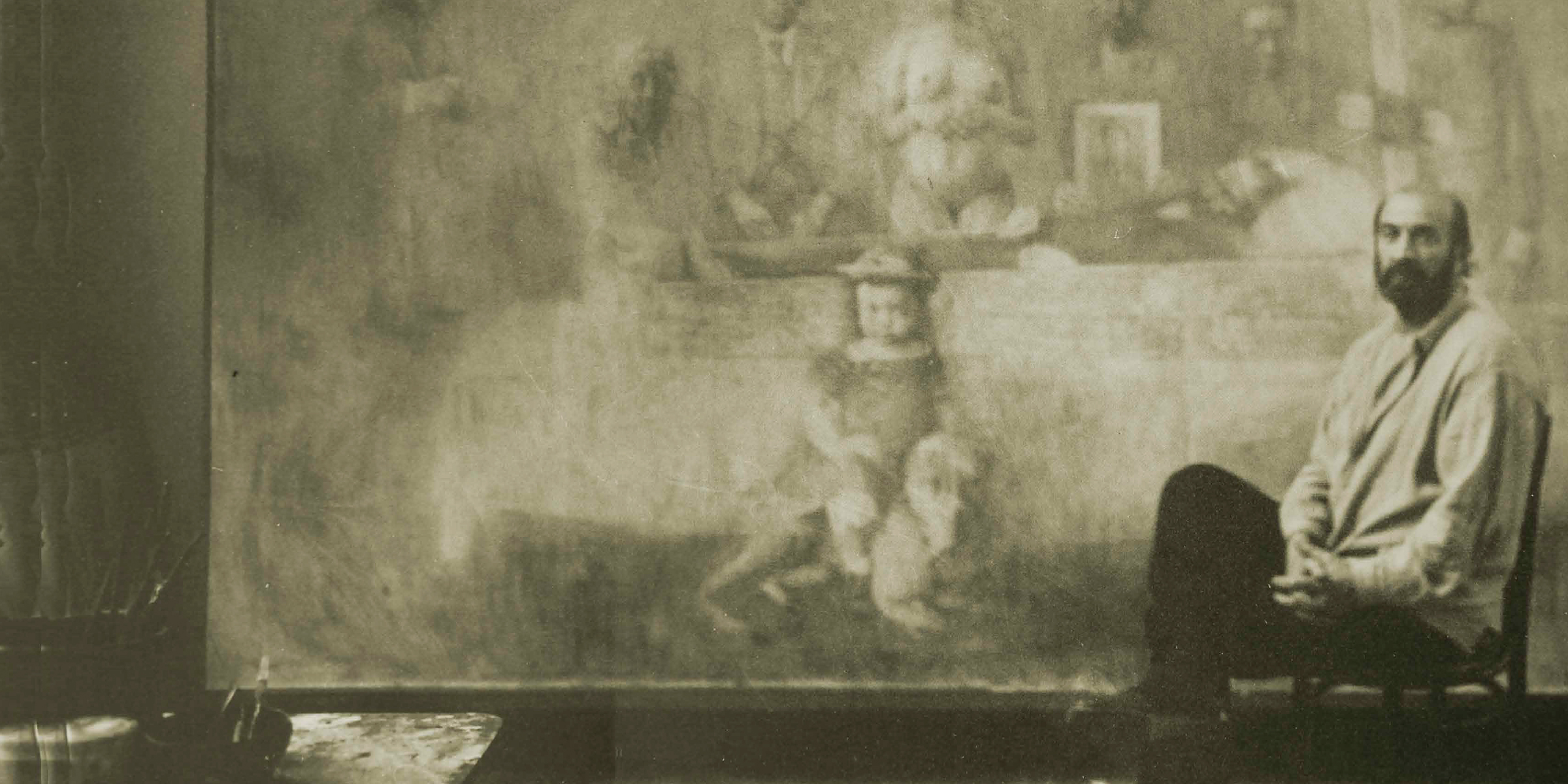

BORIS ZABOROV

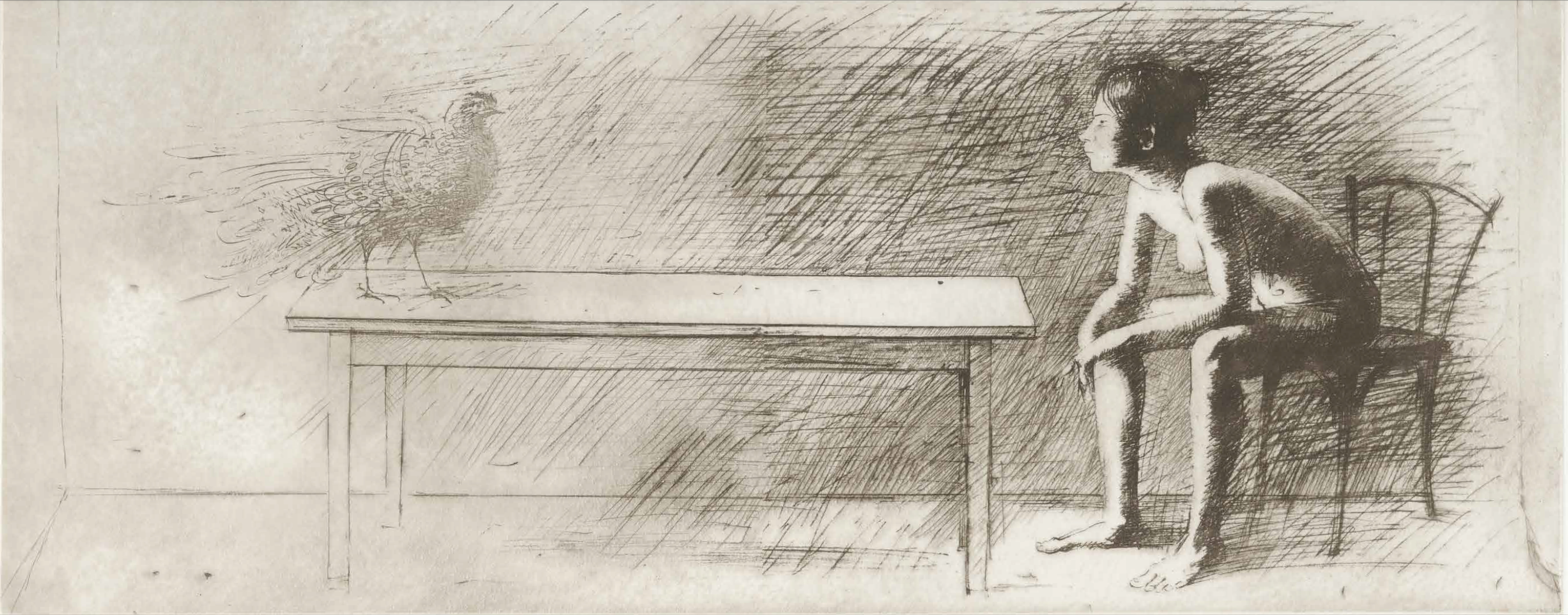

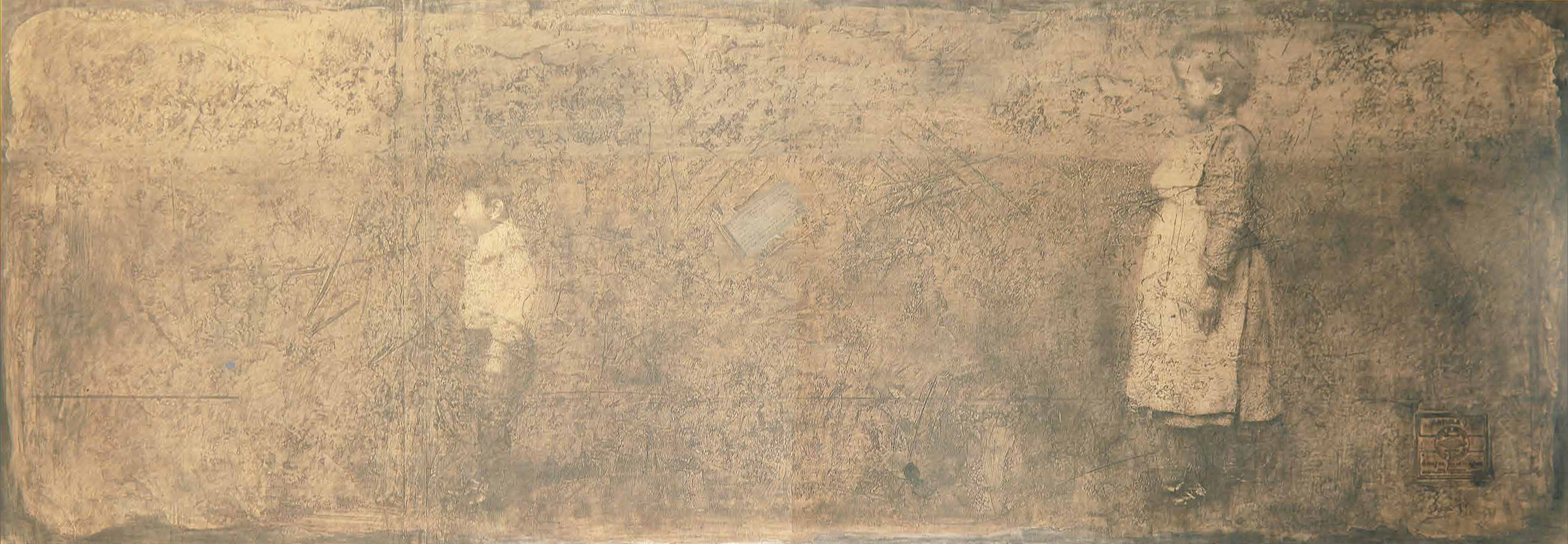

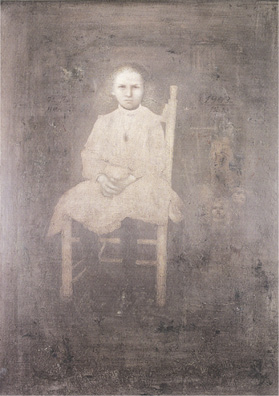

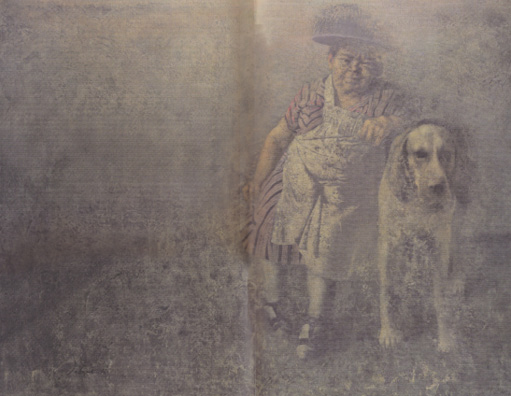

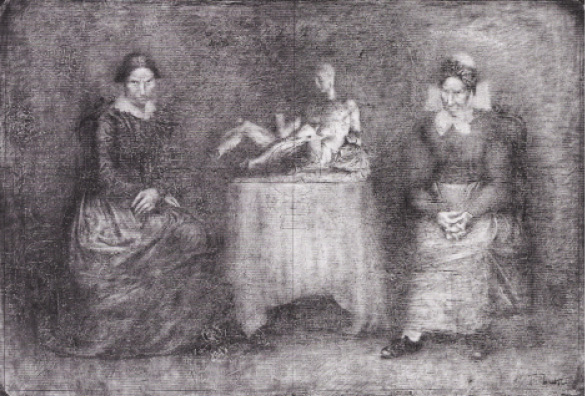

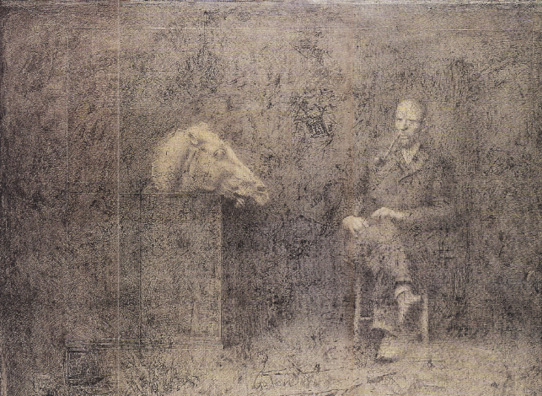

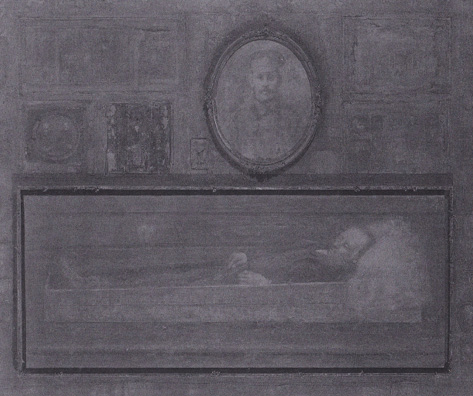

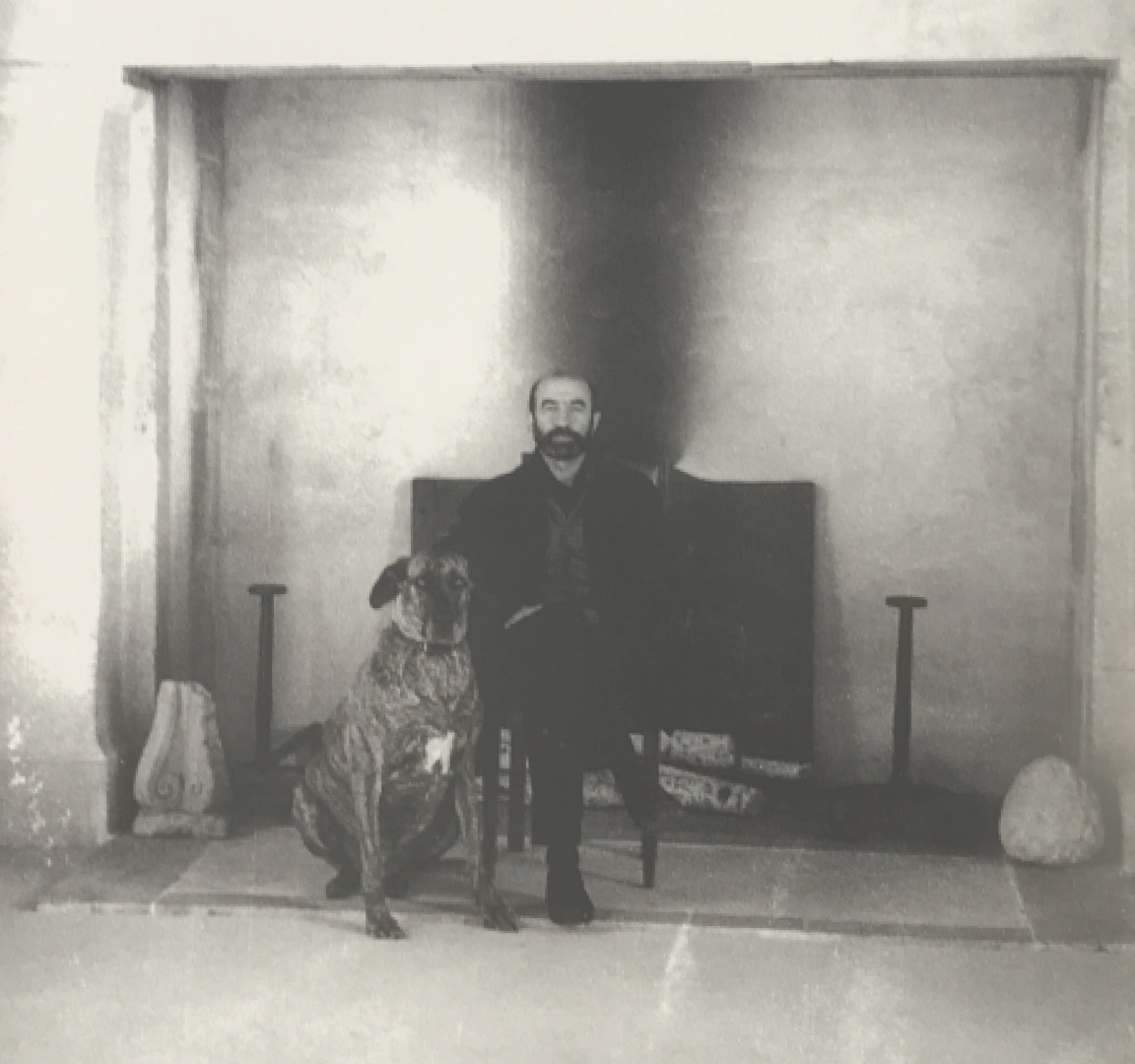

Painter, Sculptor, Graphic Artist, Scenic and Costume Designer

Born October 16, 1935 in Minsk, Belarus

Graduate of St. Petersburg State Academic Institute of Fine Arts, named after Ilya Repin

and Moscow State Academic Art Institute, named after Vasily Surikov. Diploma

Since 1981

lives and works in Paris

Chevalier of French Order of Arts and Letters

Honorary Member of the Russian Academy of Arts

Selected Personal Exhibitions

1983

Claude Bernard Gallery, Paris

1985

Retrospective. Mathildenhwhe Museum, Darmstadt, Germany

Claude Bernard Gallery, New York

1986

Art Point Gallery, Tokyo

1989

Retrospective. Palais de Tokyo, Paris

1991

Galerie K, Paris, Amsterdam

Galerie Art Point, Tokyo

1992

FIAC with Patrice Trigano Gallery, Grand Palais, Paris

1993

Patrice Trigano Gallery, Paris

1994

FIAC with Patrice Trigano Gallery, Grand Palais, Paris

1995

Retrospective. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Retrospective. “Man ge” Central Exhibition Hall, St. Petersburg

1996

Enrico Navarra Gallery, Paris

1997

O’Hara Gallery, New York

2000

Mimi Fertz Gallery, New York

2001

Art Point Gallery, Tokyo

2002

Vallois Gallery, Paris

Visconti Gallery, Paris

2004

Retrospective. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Retrospective. State Tretyakov Gallery of Russian Art, Moscow

Gallery Officina d’Arte, Verona

2006-2007

Exhibition “Eternal Book. Bronzes”. Mus e de la Monnaie, Paris

2007

Artistic Design and Installation of the Monument “Writing and the Book”

(Bronze, Height 4,5 m), Public space of the Institute of Technology “Technion” in Haifa.

Architects - Michael Seltser and Shaul Kaner

Biennale of Contemporary Art in Maastricht with Vallois Gallery, Paris

2008

“Exhibition of one painting”. Uffizi Gallery, Florence

2010

Retrospective. The National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus, Minsk

2014

“Painting, Graphics, Sculpture”. Friedman & Vallois Gallery,

New York

2015

“Etchings from Different Years. Photography”. Workshop -

Theatre of Pjotr Fomenko, Moscow

MUSEUM COLLECTIONS AND ART FOUNDATIONS

Albertina Museum, Vienna

Mathilden he Museum, Darmstadt

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

State Tretyakov Gallery of Russian Art, Moscow

The National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus, Minsk

Regional Contemporary Art Fund, Caen, Lower Normandy

Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts. Norwich, United Kingdom

Bakhrushin State Museum of Theatrical Arts, Moscow

National Centre of Costume and Scenography (CNCS). Moulins, France

Arkhangelsk Museum of Fine Arts, Arkhangelsk

F.M. Dostoevsky Literary and Memorial Museum, St. Petersburg

Marc Chagall Museum,Vitebsk, Belarus

Mus e d’art et d’histoire du Juda sme, Paris

“La Piscine”Museum of Art and Industry. Roubaix

THEATER AND CINEMA

1976

Set and Costume Design for “The Storm” by A. Ostrovskij.

Directed by L. Heifez. Janka Kupala Theatre, Minsk

1992

Costume design for “The Masquerade” by Mikhail Lermontov.

Directed by Anatoly Vasiliev. Comedie- Francaise. Paris

1994

Costume Design for “Lucrece Borgia” by Victor Hugo.

Directed by Jean-Luc Boutt. Comedie- Francaise. Paris

1996

Costume Design for “A Month in the Country” by Ivan Turgenev.

Directed by Andrei Smirnov. Comedie- Francaise, Paris

2001-2002

Set and Costume Design for “Amphitryon” by Moliere.

Directed by Anatoly Vasiliev. Comedie-Francaise, Paris

2007

Set and Costume Design for “Fahrenheit 451” after Ray Bradbury.

Directed by Adolf Shapiro. Et Cetera Theater, Moscow

2008

Script and Direction for “Sonnet”, short live action film,

starring Charlotte Rampling

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

The choice of a profession was never a problem for me.

For as long as I can remember IVe been drawing. And this has been going on for almost fifty years.

...Nothing guides me better in time

and sensation than smells. That of oil paints and linen canvas means my father. This smell, which summons up a whole pageant of memories, has never ceased to be a source of emotion and of a certain anxiety for me. I owe to my father everything good in me and the fact that I became a painter. I didn’t have time to get tired of my childhood, it vanished quickly and suddenly: I was six years old when the war began.

How many cross-roads,

sometimes strange and surprising but in the last analysis lucky, has my life had to go through for me to survive? Often, it would have been easier to perish than to come through alive, it could have happened in the Nazi concentration camp where all of my mothers family disappeared. It should have happened under the fire of the Messerschmitt machine guns aiming straight at the platform of the cargo train, crammed full of refugees. It seemed inevitable when the little slow van, which was carrying my mother, her sister, my little brother and myself, plus the archives of some regional recruiting office, found itself on a cross-road facing a German tank. And later on, many a time, from illnesses due to the cold... This period is fixed in my memory as one of terrible anxiety, expectation of danger, ceaseless activity. Apparently it is so deeply footed in my consciousness that it has become a permanent part of my vision of life.

The first year after the war

my family went back to Minsk. The city had almost entirely disappeared. Every where the eye could look, unreal pictures appeared. Rubble and burnt-down areas where solitary shapes wandered around. At sunset the city became even more disturbing and enigmatic. One would have thought it was a prehistoric landscape where, against the back-ground of the twilight sky, the silhouettes of ruined buildings took on the shape of fantastic beasts.

But in time the city came back to life.

The refugees and soldiers were coming home.

In 1950, just after my junior year at school,

I enrolled in the second year of the Minsk Fine Arts School. The students, of whom there were few, had nearly all fought in the war. They were eight or ten years older than me in age and twenty years at least in experience. I felt rather ill at ease in their midst. These were my most boring and monotonous years.

In 1953, after school,

caught up in a dream of glory like the young d’Artagnan, I rushed off to St. Petersburg. I managed to get permission to take the entrance exams at the Academy of Fine Arts. But I failed. Then, however, I remained in the preparatory class, and the following year was accepted at the Academy and entered as a first year student.

Everything was so harmonious

at that time, my age, the fact that I was a student, and the city, so beautiful in its majestic splendor. On the whole, the time I spent at the Academy was like a long holiday, a time of carefree joy. The self-contained grounds on which were situated the student dormatory, the Academy garden and the main building overlooking the Neva: all this created a sensation of privilege. This sensation, as it appeared, is in no way prejudicial to a healthy psychology. We worked in spacious, well-lit rooms. According to a teaching method formulated once and for all and- transmitted intact through generations of students, we spent long hours analyzing plaster casts and molds of antique sculptures. We could hear the buzz of the life simmering beyond the iron curtainand we considered its humdrum system with slight distain.

Today I see it as a piece of miraculous luck

that, with the help of the Almighty, the destructive energy of human passions leaves little islands of peace free from its baneful attention. These are the manuscripts, the books and the archives which do not get burned; entire cultures covered with earth waiting to come to life again; villages in the North, apparendy forgotten by God, with their unique specimens of Russian wooden architecture, paintings kept safe by the disinterested love of collectors, and many other things. These are the links in the single uninterrupted chain which constitutes our culture and which is perhaps the only justification for our existence on this earth. The old system of teaching, which was maintained at the St. Petersburg School of Fine Arts, was perhaps nothing else than a small link in this chain.

According to a long-standing tradition

at the Academy, at the end of their second year, students went to spend the summer in Crimea to paint. It was considered that after the low northern sky of Vassilievski Island it was good for the future painter to refresh on his palette under the southern sun.

This vacation in Crimea

had little effect on my palette, but it had a decisive effect on my life.

One morning, on a path

leading to the sea, I met a young girl, beautiful, tanned and slim. Since that day, and to this day we have gone ahead together. If at that time a prophet had told me that I would leave St. Petersburg and the Academy of my own free will, I would have taken him for a madman. And yet that is what happened. The young woman was studying in Moscow, and the following fall I entered the Sourikov Art Institute in Moscow, which I left in 1961.

Studies and life in Moscow

were radically different from what they had been in St. Petersburg. In the comfortable ghetto of the Fine Arts Academy, we had grown like hot-house plants, without any real contact with the outside world. In Moscow things were completely different. Our studies were only an obligation, nothing more. Each of us was looking for his place in the sun, outside the bounds of the Institute, in the bustle of Moscow’s huge population. Later in my life I was able to appreciate this experience fully.

At the end of 1961,1 went back to my native city,

Minsk, and immediately received various proposals from publishing houses to illustrate books whose titles I don’t remember. I was far from suspecting at the time that I was embarking on a road which would lead me, at the end of the 1970s, to the decision to leave my country.

I lived in a model totalitarian country,

whose pernicious ideology conditioned and penetrated all of life, and the artistic life most of all.

Illustrating books remained a relatively danger-free area,

hidden in the shadow of the literary text.

My strategy was clear: to become a painter,

to create paintings. Painting brought me satisfaction but no money. Illustrating books allowed me to live but became more and more hateful to me as time went on. All my attempts to split myself in two were in vain. I accumulated despair, exasperation and finally the fear of losing myself completely. I was tortured by the idea that each hour, each day, each year thus spent was irremediably dimishing my chances of regeneration. How could I cut this « Gordian Knot»? And so, I found myself in May 1981, on the platform of the Gare du Nord in Paris.

I arrived with a passionate desire

to begin a new life, to start again from the beginning. But this city of romantic dreams was almost a desert for me. When I looked at Paris at night with its thousands of lights, I would let myself be invaded by masochistic feelings. None of those lighted windows was thinking of me, no one was even aware of my existence. I was truly alone. Not a single thread tied me to this new world. Except the mysterious thread by which every man is attached to all of humanity.

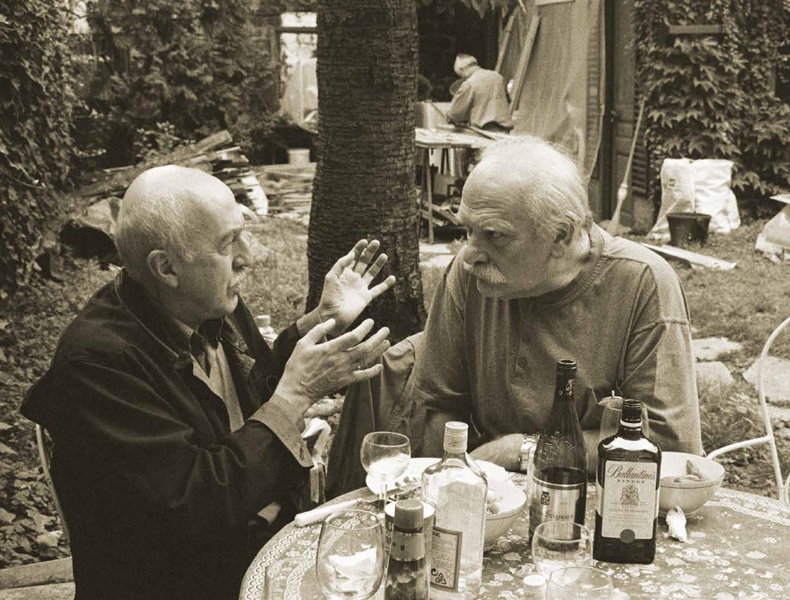

Solitude made me more aware

of the inner resonance of things. The mysterious process of the intermingling of past and present gave birth in me to the deeply nostalgic state of mind which is at the basis of my work. And so I began to work. Seven months later the contact with the Claude Bernard Gallery which was to be decisive for my life in Paris, was established. In this gallery in 1983,1 had my first individual exhibition and in the same year I received the annual prize of the city of Darmstadt in Germany. After that, this city’s museum organized an exhibition including almost all of the paintings I had done in my five years in France. Through the Claude Bernard Gallery, I was contacted by the Japanese Gallery, Art Point. And it was also at Claude Bernard that Robert Delpire saw my work for the first time. It is thanks to Robert Delpire that my first retrospective was held at the Palais de Tokyo in 1989.

Paris has long since ceased to be a desert for me.

Every day it becomes closer

to the romantic image that I had of it in my youth...

BOOKS AND CATALOGUES

1985

“Zaborov. Gem lde, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen” Retrospective

Catalogue published by Mathild-

enhehe, Darmstadt

1989

“Boris Zaborov” Retrospective

Catalogue published by Palais de Tokyo, Paris - Lausanne

1990“Boris Zaborov” Monograph. Published by Enrico Navarra Gallery, Paris

1991

“Boris Zaborov” Exhibition Cata-

logue. Published by Gallery K, Paris - Amsterdam

1995

Philippe Bidaine, Marina Bessonova, Boris Zaborov “Zaborov.”

Retrospective Catalogue.

Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow

1996

Philippe Bidaine “Zaborov.

Le Dit des Livres. Bronzes” Grafiche Aurora Edizioni, Verona

2000

“Boris Zaborov - Grands

Formats” Grafiche Aurora Edizio-

ni, Verona

2006

Michail German, Pascal

Bonafoux, Beatrice Picon-Vallin “Zaborov” Monograph.

Published by Acatos, Paris

BOOKS AND CATALOGUES

2007

Philippe Bidaine, Pascal Bonafoux “Boris Zaborov” Monograph. Published by Skira, Milano

2008

Francesco Donfrancesco, Boris Zaborov “Boris Zaborov: Ritratti d’artista” Edizioni Moretti & Vitali, Florence

2010

Boris Zaborov “Sequence of Lucky Chances, or Destiny” Published by Vita Nova, St. Petersburg

2010

“Boris Zaborov. Retrospective”

Catalogue for the Exhibition at National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus

2014

“Boris Zaborov in the eyes of the Contemporaries” Ed. d’Arte Gibralfaro, Verona - Moscow